Every game has rules. Sometimes they are simple. The children’s game tag for instance only has two basic rules:

1. Avoid whoever is “It.”

2. If you are “It”, touch (tag) someone to make them “It” and not you.

Card games, sports, board games, and videogames on the other hand, are usually much more complicated and their rules can’t be explained in under seventeen words. Perhaps as a result of this complexity, when trying to teach someone a new game, people will often tell others to simply watch them play for a while in the hopes that the newcomer will discern the basic rules. This works for most sports and card games, however, it does not cleanly translate into videogames due to the necessity of a medium for user input (i.e. controllers, mouse & keyboard, etc.). Through watching others play, a videogame player can usually learn “what” to do, but not necessarily “why” they are doing it, and certainly not “how” to do it physically.

Consequently, due to the unreliability (and often lack) of other people to teach one how to play, videogames have the burden of guiding players themselves. Nowadays, videogames have found more elegant ways of fulfilling that duty, but as most veterans of the gaming industry will attest, this was not always the case. A game from 1988 would almost always demand that a player read a bulky instruction manual, whereas modern games generally teach people how to play them through in-game tutorials. What’s more, user interfaces now display maps, objective markers, and guiding text so that players never feel lost, and worlds are usually designed to ensure that the player always finds everything they need to progress through it. This is not to say that modern games all “hold the player’s hand,” but on the whole, they are far less esoteric than most games from the 16-bit era and earlier.

With that said, not every game of the 21st century adheres to the modern design philosophy of guaranteeing that the player sees the entire game. Some titles, rather than direct the player’s progress with specific dialogue, text, or icons, rely on Conveyance: explanation through context. The player’s knowledge of the game and their current position in the game space influence their interpretation of their objectives and capabilities. Videogames with strong conveyance are designed with this in mind and thus utilize various non-verbal cues such as carefully positioned objects, camera angles, sounds, and colors to direct the player. I call these games that emphasize conveyance over directness “quiet.” They aren’t "silent," some dialogue or text is usually present in one form or another . However, what little communication there is necessitates interpretation. Rather than visually shouting at the player with large flashing arrows in the UI, they whisper by creating obstacles with easily discernable solutions, but obscured means of achieving them. Much as some math teachers might state, the methodology is more important than the solution.

Because the designer(s) have complete control over the game’s progression, they can somewhat accurately predict what the player knows and more importantly, what they don’t. This enables designers to craft specific scenarios that both teach players techniques and test their mastery of them in order to progress, all without uttering a single word. Arin “Egoraptor” Hanson thoroughly explores this concept in the 1993 Super Nintendo game Megaman X (and in a highly comedic fashion at that). However, a more contemporary and gratuitous example of this occurs in Alexander Bruce’s mind-bending first-person puzzle-platformer Antichamber.

Antichamber: Navigating the Matrix

As its genre suggests, in Antichamber you solve puzzles from the first person perspective (meaning you cannot see your avatar, only what he or she is holding) and navigate the environment by moving and occasionally jumping onto various “platforms.” However, unlike most puzzle-games which employ a single type of puzzle and iterate on it in various ways, Antichamber contains two types of puzzles: ones derived from the player’s movement and others based on manipulating colored “brick” cubes. Occasionally the two puzzle types overlap, particularly towards the end of the game, but for the most part, the puzzle varieties remain strictly divorced of each other. Both puzzle types necessitate pattern recognition, logical inferences, and (naturally) critical thinking, but their difficulty is directly tied to one’s understanding of the game’s non-Euclidean (read: utterly absurd dream world) logic as opposed to the player’s intelligence. Thus, learning this atypical logic encompasses the majority of one’s experience in Antichamber and where Bruce focuses the game’s conveyance.

NOTE: The following italicized paragraphs contain specific information about several of Antichamber’s puzzles. Because Antichamber is a puzzle game, explaining solutions to some its puzzles undermines the gameplay experience. If you would like to experience the game in its purest form, then stop reading, play the game, and read on later. Alternatively you can skip to the next section and just take my word that Antichamber has functional conveyance.

An important aspect of Antichamber is its non-linear design. The game is divided into a series of rooms, each with multiple exits and often multiple puzzles. Additionally, a player does not need to solve each puzzle they see in order to progress (ironically echoed in the game itself). With that said, almost every player’s initial foray into Antichamber is identical (provided they have never seen the game before) due to Bruce’s brilliantly mischievous conveyance.

In the first puzzle room, the player sees a large chasm and a neon “sign” of the word “JUMP!!”. Because there appears to be more land and another pathway across the chasm (as well as a wall embellished with an eye behind them, should they choose to look) the player will likely comply with the sign and jump. Unfortunately, the player will fail as the chasm is far too wide to be leapt in a single bound. Assuming that the player actually tried to reach the pathway across the chasm, she will land in front of a staircase leading to a blocked path with a door reading “the end” behind it. After desperately attempting and failing to pass the blockade, the player will turn around and see another staircase leading to an open path across the same chasm. Here, most players will attempt to jump the chasm again because the gap is slightly smaller and there are no visible pathways across the gap. Once again the player will fail to reach the other side, but this time they will finally land at the bottom of the chasm. From here, the player will see a single open path into darkness preceded by a black sign on a wall with the words “click here” written on them. At this point the player may start to become skeptical of signs, but will likely click it anyway out of a rising need for guidance. Upon clicking the sign, the player will see an amusing picture followed by the reassuring words: “failing to succeed does not mean failing to progress.”

In the first puzzle room, the player sees a large chasm and a neon “sign” of the word “JUMP!!”. Because there appears to be more land and another pathway across the chasm (as well as a wall embellished with an eye behind them, should they choose to look) the player will likely comply with the sign and jump. Unfortunately, the player will fail as the chasm is far too wide to be leapt in a single bound. Assuming that the player actually tried to reach the pathway across the chasm, she will land in front of a staircase leading to a blocked path with a door reading “the end” behind it. After desperately attempting and failing to pass the blockade, the player will turn around and see another staircase leading to an open path across the same chasm. Here, most players will attempt to jump the chasm again because the gap is slightly smaller and there are no visible pathways across the gap. Once again the player will fail to reach the other side, but this time they will finally land at the bottom of the chasm. From here, the player will see a single open path into darkness preceded by a black sign on a wall with the words “click here” written on them. At this point the player may start to become skeptical of signs, but will likely click it anyway out of a rising need for guidance. Upon clicking the sign, the player will see an amusing picture followed by the reassuring words: “failing to succeed does not mean failing to progress.” Now, the dark path in front of the player is lit up by two white lines that a now cautious player will likely follow. Upon doing so, she will arrive at a room with two adjacent staircases, one blue staircase leading up and another red staircase going down. The player may also notice another “click me” sign to their right which reads: “a choice may be as simple as going left or going right.” The player will then choose a staircase for whatever arbitrary reason, and upon following the linear path way to its conclusion, will end staring at the same two staircases. Likely out of bewilderment, the player will then try the other staircase only to again, find themselves in front of the two staircases. At this point the player will likely become slightly frustrated and double back to see if they missed anything (an observant player might also notice that a new sign has appeared reading “the choice doesn’t matter if the outcome is the same”). Here the player will see that the path has changed as well as a new sign reading “things aren’t always as we remember them.” Following this new path however will lead to a red laser at waist height preceding a closed door. Seeing that there’s only one way to go, the player will probably try and pass the laser, opening the door. Behind said door however is another laser. Seeing that the first laser only opened the door behind them, the player might (accurately) guess that this laser will close it. Unfortunately passing through this laser inadvertently traps the player in the room, as this laser only closes the door behind them, but does not open it. The only thing in this new empty white room is a picture of an Esc key and yet another sign displaying the snarky text: “some choices leave us running around a lot without really getting anywhere,” as well as a picture of a finger pushing an Esc key. There is literally nothing that a player can do in this room other than push the Esc key. Doing so then takes the player back to the first room of the game where they can re-enter the Antichamber and try again to find the exit.

Now, the dark path in front of the player is lit up by two white lines that a now cautious player will likely follow. Upon doing so, she will arrive at a room with two adjacent staircases, one blue staircase leading up and another red staircase going down. The player may also notice another “click me” sign to their right which reads: “a choice may be as simple as going left or going right.” The player will then choose a staircase for whatever arbitrary reason, and upon following the linear path way to its conclusion, will end staring at the same two staircases. Likely out of bewilderment, the player will then try the other staircase only to again, find themselves in front of the two staircases. At this point the player will likely become slightly frustrated and double back to see if they missed anything (an observant player might also notice that a new sign has appeared reading “the choice doesn’t matter if the outcome is the same”). Here the player will see that the path has changed as well as a new sign reading “things aren’t always as we remember them.” Following this new path however will lead to a red laser at waist height preceding a closed door. Seeing that there’s only one way to go, the player will probably try and pass the laser, opening the door. Behind said door however is another laser. Seeing that the first laser only opened the door behind them, the player might (accurately) guess that this laser will close it. Unfortunately passing through this laser inadvertently traps the player in the room, as this laser only closes the door behind them, but does not open it. The only thing in this new empty white room is a picture of an Esc key and yet another sign displaying the snarky text: “some choices leave us running around a lot without really getting anywhere,” as well as a picture of a finger pushing an Esc key. There is literally nothing that a player can do in this room other than push the Esc key. Doing so then takes the player back to the first room of the game where they can re-enter the Antichamber and try again to find the exit.This highly specific experience is shared by almost every player of this game despite there actually being over a dozen other pathways simultaneously available. Why? Because the player doesn’t know the logic of the world yet, and consequently will rely on the logic of the reality they physically live in. When one sees a very large gap in a game space and knows that they don’t have the capability of flight, they would assume that the only way to cross it is to jump. In Antichamber however, most large gaps (including both of the chasms that the first time player would attempt to jump) are crossed by simply walking, walls with eyes on them dissipate if one stares at them long enough, darkness often hides other paths, and wall posters do not provide guidance, but reflective commentary. Over time, every player learns all this and more. However, their acquisition of this knowledge invariably stems from Bruce’s carefully crafted scenarios that gradually leads players to make and learn from their mistakes in order to understand the unique rules of Antichamber’s non-Euclidean world. This silent, artful manipulation encompasses the core ethos of designing a quiet game. Due to the relatively uncommon use of this methodology as the primary means of communication, however, quiet games initially seek to communicate the methods in which it will speak to them.

Antichamber, for instance, begins not with credits or a title screen, but by immediately spawning the player in a cubic wire-frame room with three black screens and one translucent glass screen encompassing each wall . The immediately visible screen contains a picture of a sleeping human fetus with the portentous text: “every journey is a series of choices. The first, is to begin the journey,” while the other screens display the game’s control scheme, how to enter the first puzzle room, and a separate room behind the glass that leads to an exit. In less than ten seconds and without a single line of spoken dialogue, this first room alone teaches the player how to interact with the world (the control scheme and the first puzzle room), mentally situates her to explore and make decisions (the picture and accompanying text), demonstrates how it will directly communicate with the player (again, the picture and text), and provides a goal for the player to reach (the exit).

Antichamber, for instance, begins not with credits or a title screen, but by immediately spawning the player in a cubic wire-frame room with three black screens and one translucent glass screen encompassing each wall . The immediately visible screen contains a picture of a sleeping human fetus with the portentous text: “every journey is a series of choices. The first, is to begin the journey,” while the other screens display the game’s control scheme, how to enter the first puzzle room, and a separate room behind the glass that leads to an exit. In less than ten seconds and without a single line of spoken dialogue, this first room alone teaches the player how to interact with the world (the control scheme and the first puzzle room), mentally situates her to explore and make decisions (the picture and accompanying text), demonstrates how it will directly communicate with the player (again, the picture and text), and provides a goal for the player to reach (the exit).Essentially, this first room provides one with the videogame equivalent to exposition: basic rules and a win condition. Without it, the player would have no idea how to play or what to do. An astute player, however, will notice that this information does not explain why the player is seeking the exit. Though Antichamber is uncharacteristically blunt in the way it informs players about its overarching control scheme and coquettishly dangles the player’s ultimate goal in its first room, it refrains from illustrating the context in which those controls will be used or why the player needs to seek the exit, providing the player with room to explore the rules of the game as well as the world governing them in order to discover the purpose for himself.

This deliberate obfuscation of the player’s purpose illustrates another of the key differences between quiet and conventional games. Conventional games are (usually) designed with the notion that the player wants to have “fun.” So, to best serve that goal, they attempt to communicate their rules as clearly as possible, such that the player can most easily act according to them. Essentially, players can concentrate on playing the game as opposed to understanding its finer points. In contrast, quiet games demand that the player think critically about each and every component of the game and their capabilities within it. They provide naught but the barest fragments of necessary information so that one can potentially discover the rest. This is not to say that these games are designed against the player or leave her to hopelessly wander in search of purpose. Rather, they require players to intellectually invest themselves in the game in order to engage with it on its most basic levels. As with most things in life, this intellectual investment generally leads to an emotional investment, which, in the interactive videogame medium, often manifests itself as personal interest in the game’s narratives.

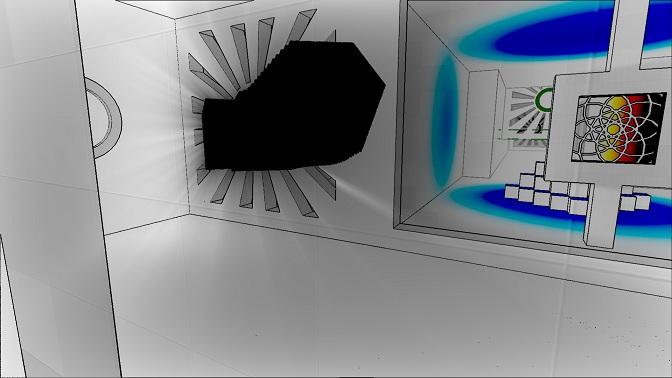

Antichamber demonstrates this mental procession through its presentation of the brick tool and its accompanying upgrades. The player first sees the brick tool, a futuristic looking gun that manipulates “bricks,” behind a translucent wall. Upon gazing at it, a floating glowing black cube will appear from a door in the adjacent room accompanied by mysterious whispering. The cube then floats through the adjacent room, passing through the brick tool and through out of the room through another door. Because this black cube is the first (and only) thing in the game that can move and open doors (other than the player) it appears to have some sort of will. Willpower implies intelligence and due to the ominous nature of the audio-visual elements surrounding the cube, a player will rightfully feel curious (and probably frightened) by the mysterious sentient being they observed. This mystery sparks one’s imagination that there is something more to the antichamber than they can currently observe. Each upgrade to the brick tool as well, is preceded by an encounter with the floating black cube just outside of the player’s reach. Indeed, the mystery proffered by this seemingly sentient object quietly suggests a narrative in which the player’s apparent need to escape the antichamber holds larger significance to the game’s story, and that implied narrative assists in motivating the player to continue playing the game.

Antichamber demonstrates this mental procession through its presentation of the brick tool and its accompanying upgrades. The player first sees the brick tool, a futuristic looking gun that manipulates “bricks,” behind a translucent wall. Upon gazing at it, a floating glowing black cube will appear from a door in the adjacent room accompanied by mysterious whispering. The cube then floats through the adjacent room, passing through the brick tool and through out of the room through another door. Because this black cube is the first (and only) thing in the game that can move and open doors (other than the player) it appears to have some sort of will. Willpower implies intelligence and due to the ominous nature of the audio-visual elements surrounding the cube, a player will rightfully feel curious (and probably frightened) by the mysterious sentient being they observed. This mystery sparks one’s imagination that there is something more to the antichamber than they can currently observe. Each upgrade to the brick tool as well, is preceded by an encounter with the floating black cube just outside of the player’s reach. Indeed, the mystery proffered by this seemingly sentient object quietly suggests a narrative in which the player’s apparent need to escape the antichamber holds larger significance to the game’s story, and that implied narrative assists in motivating the player to continue playing the game.Unfortunately, at the end of the game, after a gauntlet of puzzles that test literally every skill in the game, the mystery remains unresolved; no narrative reveals itself. The player is appropriately rewarded for demonstrating their mastery over the game with a face to face encounter with the black cube. Unable to physically touch it, the only thing a player can do is attempt to manipulate the cube with the brick tool. As he attempts acquire the cube, the antichamber around him dissolves into the white abyss, revealing a lone bridge leading to monolithic spires in the distance. With nowhere else to go, the player crosses the bridge, falls up the spire (remember, this world has its own logic), and leaps into the white void to finally find a cube shaped recess for the black cube. Upon placing the cube, a dome erects around the player and various columns inside the forming dome, arrange themselves in the form of the game’s logo. And that’s the end. Roll credits.

So many new questions are posed by this final sequence of the game, yet none of them are answered in the game space (or outside of it for that matter). Regardless of where one falls on the spectrum of disappointment, this ending disillusions the player into recognizing that the game is less than it appeared. From this unrewarding scenario one can discern at least three things. The first is that the lack of concrete details elucidated by quiet games’ narratives encourages players to impose their own imagination on the game space in order to fill in their gaps in understanding. Wolfgang Iser discusses this phenomenon in his seminal essay “The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach”:

“The unwritten aspects of apparently

trivial scenes and the unspoken dialogue within the ‘turns and twists’ not only

draw the reader into the action but also lead him to shade in the many outlines

suggested by the given situations , so that these take on a reality on their

own. But as the reader’s imagination animates these ‘outlines,’ they in turn

will influence the effect of the written part of the text. Thus begins a whole

dynamic process: the written text imposes certain limits on its unwritten

implication in order to prevent these from becoming to blurred and hazy, but at

the same time these implications, worked out by the reader’s imagination, set

the given situation against a background which endows it with far greater

significance than it might have seemed to possess on its own. In this way

trivial scenes suddenly take on a shape of an ‘enduring form of life.’ What

constitutes this form is never named, let alone explained in the text, although

in fact it is the end product of the interaction between text and reader.”

Works Cited:

Iser, Wolfgang. “The Reading Process: A Phenomenological Approach.” Critical Theory Packet, English 450. Spring 2014. 1002-14.

You can buy the games here:

http://www.antichamber-game.com/

Originally Written: June 24, 2014

Initially Posted: June 25, 2014

Last Edited: June 25, 2014